Shrnutí:

- Jelikož pandemie Covid-19 tlačí globální ekonomiku do nejhorší recese od druhé světové války, systémová sociální rizika by se mohla stát důležitějším faktorem pro politické riziko a v některých zemích zhoršit i podnikatelské prostředí.

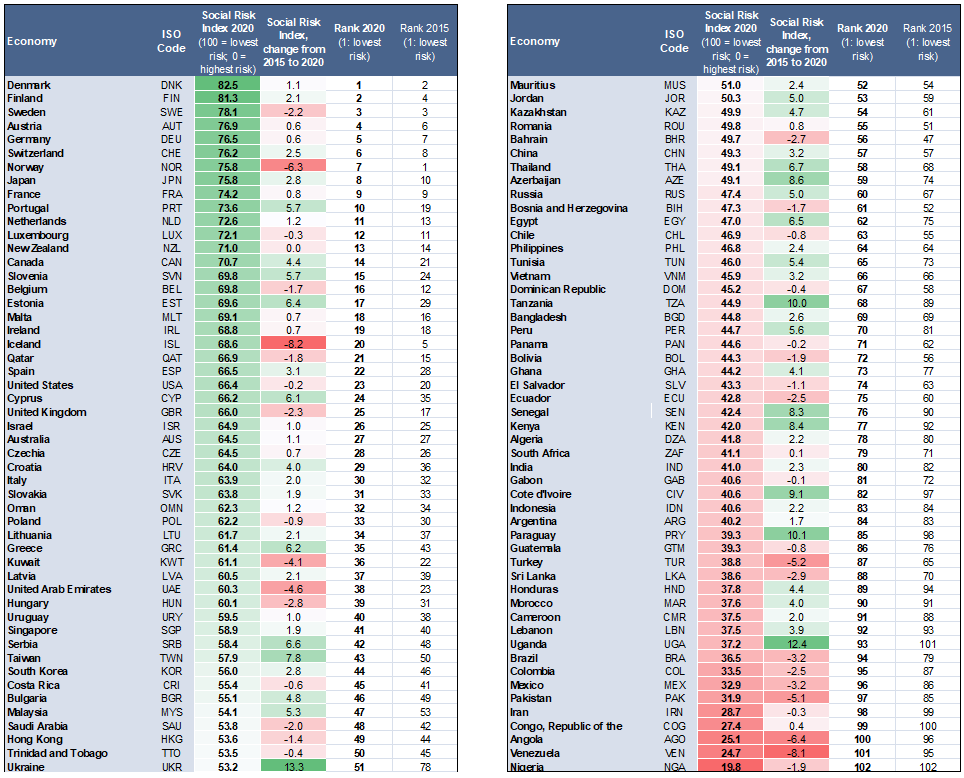

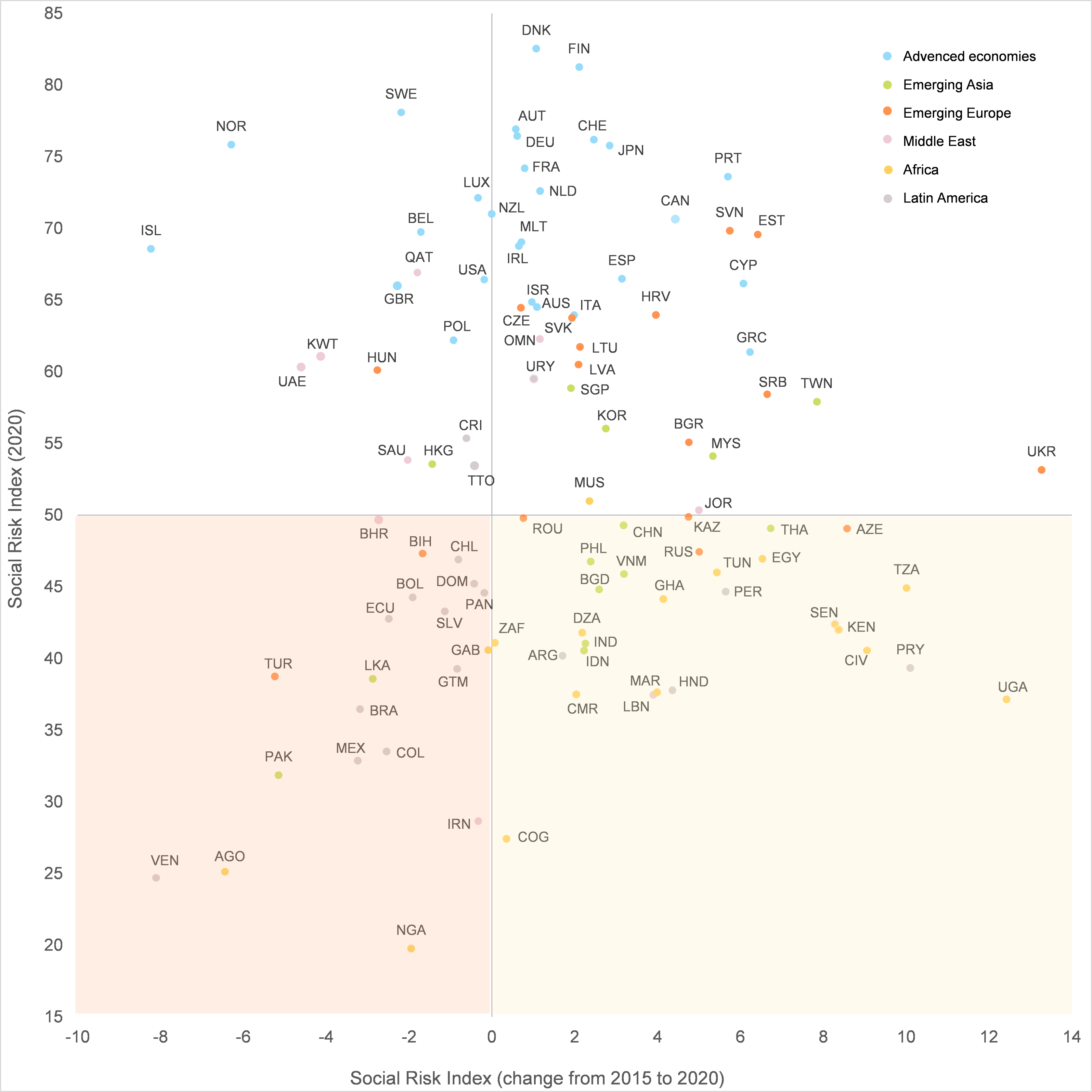

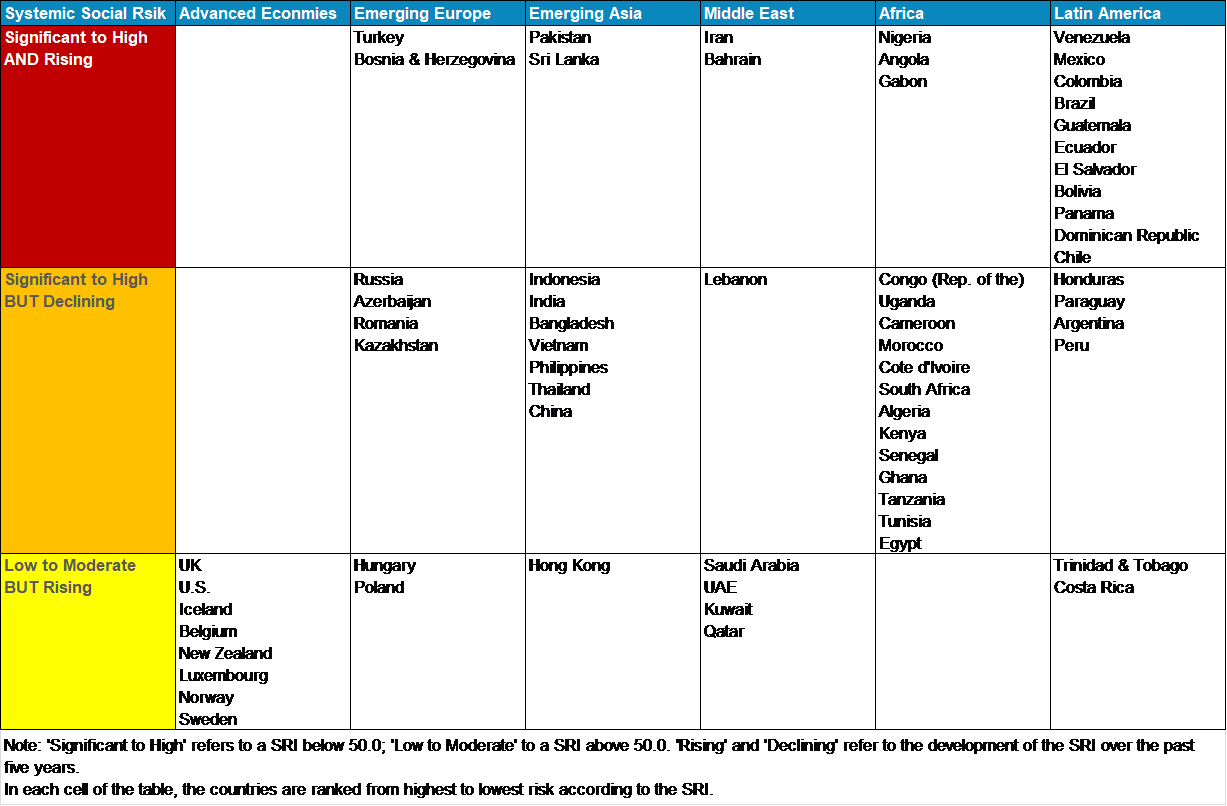

- Vytvořili jsme index sociálních rizik (SRI - Social Risk Index), abychom zjistili, které země jsou obzvláště zranitelné vůči systémovým sociálním rizikům včetně událostí, jako jsou protivládní protesty a jiné incidenty, které by se mohly stát faktorem změny v politice i v podnikání a rozhodování o investicích. SRI zahrnuje strukturální determinanty, které měří základní silné a slabé stránky a vnímání politického, institucionálního a sociálního rámce pro 102 zemí, přičemž jejich klasifikace je v rozmezí od 0 (nejvyšší riziko) do 100 (nejnižší riziko).

- SRI neměří pravděpodobnost sociální krize ani nepředpovídá budoucí sociální nepokoje. Jde spíše o ukazatel zranitelnosti, který se zaměřuje na dlouhodobější strukturální determinanty sociálního rizika.

- Dánsko, Finsko a Švédsko jsou tři země s nejvyšší hodnotou SRI v roce 2020 a vykazují nejnižší úrovně sociálního rizika. Německo je na 5. místě a Francie na 9. místě.

- Nigérie, Venezuela a Angola vykazují nejvyšší míru sociálního rizika v našem vzorci. Venezuela a Angola patří k těm zemím, kde za posledních pět let došlo k nejvýraznějšímu zhoršení.

- Vyspělé ekonomiky (AE - Advanced Economies) jsou obecně méně zranitelné vůči systémovým sociálním rizikům jako rozvíjející se trhy (EM - Emerging Markets), přičemž Řecko (35. místo) a Itálie (30. místo) se umístily nejnižší ze všech vyspělých ekonomik.

- Nejlépe hodnocené rozvíjející se trhy jsou Slovinsko (15. místo), Estonsko (17. místo) a Katar (21. místo). Česká republika je na místě 28.

- Z regionálního hlediska jsou ekonomiky z rychle se rozvíjející Evropy umístěny v průměru nejlépe, zatímco v blízké budoucnosti vykazuje nejvyšší míru sociálního rizika Afrika a Latinská Amerika

VÍCE SI PŘEČTĚTE V REPORTU V ANGLIČTINĚ

VÍCE SI PŘEČTĚTE V REPORTU V ANGLIČTINĚNew Dimensions of Social Risk

Social and political risk were already on the rise in a number of countries and regions well before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. In some cases, this was not surprising. In Venezuela, for example, long-lasting political and economic mismanagement had resulted in mass anti-government protests for several years. Iran had also seen anti-regime rallies before. And in Argentina, a textbook Emerging Markets (EMs) crisis led to a rapidly and painfully unravelling of macroeconomic imbalances, which aggravated already difficult social conditions. However, the wave of strong and durable anti-government demonstrations in Hong Kong, Lebanon and across Latin America (notably in Ecuador, Chile, Bolivia and Columbia) in the second half of 2019 was sudden and unexpected. In particular, the intensity of unrest in high-income EMs such as Chile and Hong Kong surprised markets. Moreover, anti-government protests also appeared to have increased in Advanced Economies (AEs). In particular, the Yellows Vests movement against fiscal austerity in France that began in late 2018 caught a lot of attention and sparked copycats in several other countries. Overall, this suggests that not only the overall level of economic wealth in a country but also the distribution of that wealth, changes in the level of welfare, as well as subjective perceptions of the country’s government and institutions, play a role with regard to social risk.

Most of the 2019 protest movements continued into early 2020 until the Covid-19 pandemic struck, resulting in especially strict lockdown measures that have largely starved them off for some time. But as stage two of the Covid-19 crisis – the gradual opening of national economies – has begun, there is a significant likelihood that protests in both EMs and AEs arise anew. Moreover, social discontent and unrest may be aggravated and could also spread to other countries that have been politically calm in recent years as a result of the impacts of the Covid-19 crisis. People who have given their governments the benefit of the doubt in phase one of the crisis (full or partial lockdowns to ‘flatten the curve’) may now become unsatisfied with the preparedness of authorities or the pace of de-confinement as the economic pain is growing. A generally poor health situation, increasing unemployment and poverty, rising prices (especially for food) as well as a weak government response to the crisis due to mismanagement or lack of fiscal resources may add to already existing social risks.

Already in the course of May, there have been protests and demonstrations around the world against government responses to the ongoing pandemic, and these protests have also drawn opposition from those who think the lockdowns have been justified. For the moment, these protests mostly appear to represent ‘social noise’ rather than severe social unrest. However, it cannot be ruled out that this noise develops into more serious and lasting protests, or that it occurs in countries that have been calm for now.

In this paper, we will identify those countries that are most vulnerable to systemic social unrest in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, i.e. in the next 18 months or so. For this purpose we have developed a Social Risk Index (SRI) that identifies underlying strengths, weaknesses and perceptions of a country’s political, institutional and social frameworks, signaling the general vulnerability to ’systemic social unrest‘. The latter comprises events that could become game-changers with regard to politics and policymaking, as well as business and investment decisions.

The focus of the analysis will be on 102 selected economies, including all AEs and the larger EMs. We have also calculated the Social Risk Index backwards for the year 2015 to analyze the change over the past five years per country and identify the potential for rising social discontent that could trigger unrest even in wealthier countries.

For details on the methodology of the Social Risk Index, see Box 1.