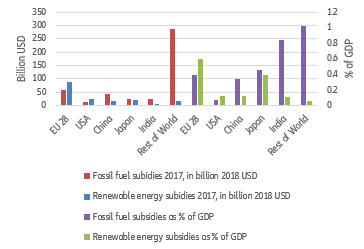

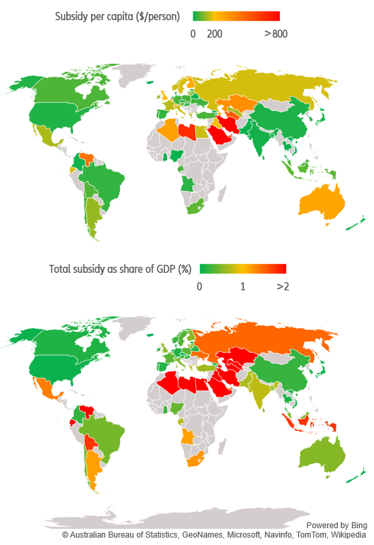

Abolishing fossil fuel subsidies and directing the funds to renewable energy seems like an easy win for the climate: After all, fossil fuel subsidies account for 0.5% of global GDP, almost exactly the size of the funding gap needed to comply with the Paris Accord . But getting rid of them comes with steep costs for consumers, particularly the poorest households. Estimates from the OECD and IEA put the total value of fossil fuel subsidies at USD468bn as of 2019 (for 81 countries). Figure 1 shows that these subsidies outpace those for renewable energy in most countries, with the EU-28 and the US being notable exceptions. As shown by Figure 2, the most likely determinant is the presence of a large domestic fossil fuel industry, which tends to have strong political and lobbying power in many countries. Exceptionally high subsidies are thus paid in the MENA region (Middle East & North Africa) as well as in Australia and Venezuela (see Appendix for further details on methodology, segments of fossil fuel subsidies).

Figure 1 – Comparison of global fossil fuel vs. renewable energy subsidies

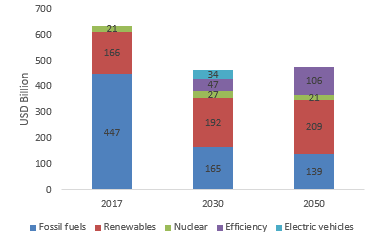

While fossil fuel subsidies have been declining at the global level, the trend is not nearly sufficient to reach climate ambitions. IRENA’s estimates suggest that fossil fuel subsidies will have to fall below USD139bn by 2050 for a 1.5°C compatible energy transition pathway (Figure 3). More than half of current fossil subsidies benefit petroleum products . IRENA projects total energy subsidies (renewable and fossil) to decline by 26% until 2030 and stabilize from 2030 onward, since the 69% drop in fossil fuel subsidies will not be fully compensated by the increase in renewable subsidies. The main reason is that renewable energy will become cheaper and thus require relatively less state support. As this cost deflation is largely driven by economies of scale, a larger share of the cost burden will fall on the first movers. A broad and coordinated effort with developed economies, as well as China and India in the lead, would allow for a fair distribution of the initial burden.

Figure 2 – Global view of fossil fuel subsidies: top per capita; bottom per GDP

The persistence of subsidies for fossil fuels stems from the political and lobbying power of the sector in many economies, along with the slower pace of energy transition that we expect in emerging economies. Subsidies persist for several reasons: lack of disclosed information regarding their amount, distribution and effects; weak institutions unable to better target them; lack of confidence in the government’s use of fiscal revenues from abolishing them (especially in countries prone to corruption); concerns over the harmful impact on the poor and the general economic impact (inflation, competitiveness) or weak macroeconomic conditions.

Figure 3 – Expected future development of energy subsidies

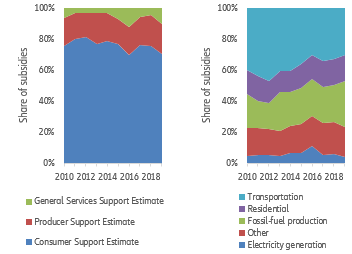

However, abolishing these subsidies outright is also politically sensitive: Most subsidies benefit consumers (Figure 4, left) who would probably object to the reductions, at least on the ballot if not on street. This concern is also supported by the sectoral composition of the subsidies (Figure 4, right). The largest share of subsidies goes to the transportation sector, which particularly benefits consumers, as does the support for the residential sector.

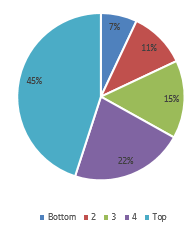

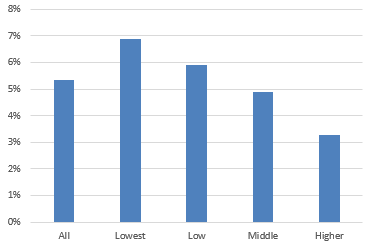

Reports from the World Bank and the IMF show that fossil fuel subsidies are regressive and mainly benefit higher-income groups, which tend to consume more energy than poorer households. According to the IMF, universal fuel subsidies are inefficient as the richest 20% of households receive, on average, about six times as much subsidies as the poorest 20% (Figure 5). To support the poorest 40% of households with USD1 through gasoline subsidies, a total of USD14 of subsidy-related expenditures is necessary . Moreover, as subsidies come from the general tax base, this situation creates a wealth transfer from poorer to richer people . But at the same time, poor households are as strongly affected in relative terms as their energy-related expenditures consume almost twice the share of their household incomes (nearly 7%), compared to that of the richest quartile of households (Figure 6).

Figure 4 – Fossil fuel support by beneficiary (left) and by sector (right)

(50 countries)

In this context, abolishing fossil fuel subsidies requires a holistic approach to secure a just transition. Abrupt measures will not work. What is required are comprehensive plans for phasing-in and sequencing price increases to enable the whole population to smoothly adjust. This has to be accompanied by targeted cash transfers to poor households, e.g. expanded safety net programs, temporarily maintained universal subsidies on commodities used by poor households or increased spending on programs benefiting primarily the poor (targeted health, education or infrastructure expenditures).

Figure 5 – Distribution of subsidy benefits by consumption groups (quintiles) in percentage

Several countries are currently working on implementing such solutions to remove fossil fuel subsidies and use fiscal revenues elsewhere. For example, the World Bank helped Egypt adjust electricity tariffs and to phase the elimination of fuel subsidies between 2014 and 2019. It also contributed to fossil fuel subsidies reform in Ukraine, which included gas and district heating tariff increases compensated by the expansion of targeted safety net programs. The Philippines, Indonesia, Ghana and Morocco introduced cash transfers and social safety net expansions for poor families to compensate for the removal of subsidies. According to a study from the International Institute for Sustainable Development, 53 countries took steps to reform their fossil fuel consumer subsidies or to increase taxation on fossil fuels between 2015 and 2020 .

Figure 6 – Share of household income spent on energy consumption

Countries that tried to implement such reforms without applying these steps have faced significant popular protests, emphasizing how sensitive the access to affordable energy can be for most people. The abrupt removal of fossil fuel subsidies in Ecuador in 2019 triggered massive public outrage, mostly due to the sudden increase of gasoline and diesel prices. A diesel and gas price hike in Mexico in 2017 also ignited violent protests and disrupted the economy. And even in France, a developed country, fuel tax increase lit up the Yellow Vest movement. In such situations, governments are often tempted to backpedal rather than pursuing their reform efforts.