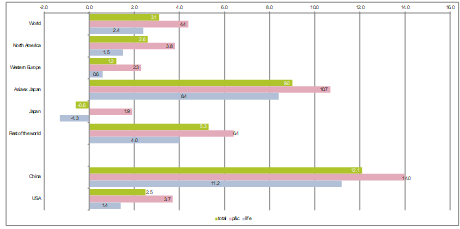

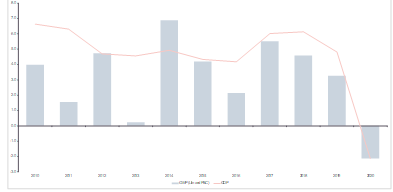

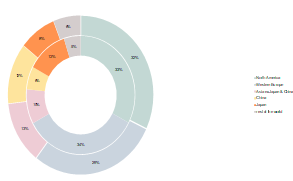

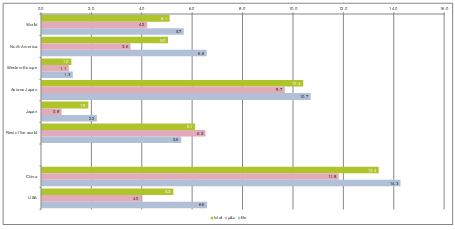

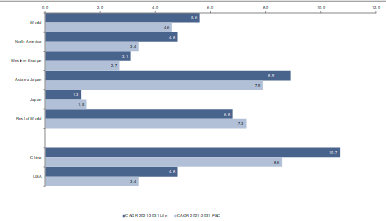

In the US, President Biden’s stimulus packages are set to propel domestic demand. Adding the successful vaccination campaign and the healthy progression of housing prices, consumer confidence is set to increase significantly. On the back of this confidence boost, accompanying steady progress on the job front, we expect a big chunk of excess savings to be unleashed, generating a strong impetus for consumption, the main driver of the US economy. All in all, we expect the US economy to grow by +5.3% y/y in 2021 and +3.8% y/y in 2022. Fiscal policy, however, could turbo-charge growth even further. On top of the first USD1.9trn stimulus package, the US government wants to add another round of stimulus with a USD2.3trn infrastructure program to renovate roads and bridges and develop new types of green and digital infrastructure, while continuing to invest in health and education to reduce inequalities. Should the second leg of the plan be implemented in full, it has the potential to boost growth significantly above +6% y/y in 2021 and +4% y/y in 2022.

Europe remains the recovery laggard compared to other economic heavyweights. In 2021, we expect the European economy to race at a rapid pace through the entire economic cycle, from a double-dip recession at the start of the year – due to renewed lockdowns – to a consumption-led catch-up growth spurt in the second half of the year when progress on the vaccination front should allow for an economic reopening. Thankfully, strong export demand – driven by the ongoing Chinese recovery and super-charged, stimulus-induced US GDP growth – will extend a helping hand to European economies in 2021, in turn exacerbating the divergence between manufacturing and services. At the same time, policymakers will continue to do “whatever it takes” to safeguard the recovery and shore up public support ahead of key elections in Germany (September 2021) and France (April 2022). All in all, we expect Eurozone GDP to expand by +4.0% in both 2021 and 2022. That means that the Eurozone economy is set to recover to pre-crisis GDP levels only in H1 2022, almost a full year after the US.

In China, the post-Covid-19 recovery is well underway, and 2021 will focus on policy normalization. The 2020 rebound was mostly a story of policy-driven areas such as the real estate and infrastructure sectors. In 2021, household consumption and business investment could become the growth drivers. The external environment will continue to be supportive as many of China’s trading partners are still battling the pandemic and their policies are in full easing mode. We expect the Chinese economy to grow by +8.2% in 2021 (after +2.3% in 2020) and +5.4% in 2022. This means that the official target of “above 6%” will be relatively easy to achieve, allowing policymakers to shift their focus away from short-term stimulus to financial vulnerabilities and asset price bubbles (in real estate and capital markets). The normalization, however, will be done in a flexible and gradual manner: fiscal measures, for example, will boost the economy by “only” 4.6% of GDP in 2021, after 7.1% in 2020, but 2.9% on average in 2018-2019.

Turning to monetary policies, most central banks will continue with their expansionary measures in 2021, with the notable exception of China, where the policy stance already started to tighten in Q4 2020. In the US and Europe, on the other hand, policy normalization will proceed at a very gradual pace. The US Federal Reserve might kick off with a first tapering step in H2 2022, while the the European Central Bank will clearly lag as growth and inflation trail behind. The first interest rate hikes in the Eurozone may have to wait for late 2023 or 2024.

Nonetheless, against the backdrop of stronger confidence in the global recovery and rising inflationary pressure, yields have risen since the beginning of the year. 10y US Treasuries, for example, jumped by a whopping 70bp to 1.6%; at this level, expectations for a strong recovery already seem to be priced in. Accordingly, we expect 10y US Treasuries not to exceed current yield levels at the end of the year, though higher volatility is very likely. A similar development is expected in Europe (but at a lower level): yields of the 10y German Bund will remain broadly unchanged over the year and only rise moderately in 2022.

In this context, we expect equity markets to close the year with timid single digit returns but to accelerate in 2022 on the back of a palpable economic recovery and still accommodative monetary policy. European risky assets could even find themselves in a favorable position, offering more upside potential than their US counterparts due to the delayed recovery.

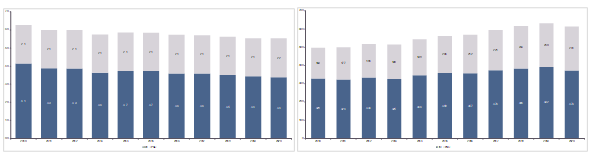

All in all, the economic environment should provide the insurance industry with some tailwinds in the next few years. While capital markets remain challenging as the long yield winter is likely to continue and volatility stays elevated, income and investment are growing, building the bedrock for rising demand for insurance.

Insurance and Inflation

There is, however, one drag: Inflationary pressures will continue to increase in 2021 for several reasons: first, the recent input cost bonanza, driven above all by strained supply chains and the oil price recovery; second, higher services inflation along with the economic reopening in H2 and third, strong pandemic-related roller coaster base effects. Although the likelihood that inflation embarks on a structural upside trend remains low, even a temporary return of inflation, after years of hibernation, might pose some challenges for the insurance industry.

There are basically four channels through which inflation can impact insurance profitability, the claims channel being the most prominent: inflation leads to higher claims costs, eroding profitability. The more sudden the inflation surge, the more severe the impact as premiums cannot be adjusted. The other three channels are expenses, investment income and the balance sheet. Among these three, however, only expenses are a clear negative, in particular if rising wages are not matched by rising productivity. Investment income, on the other hand, could even be positively influenced if inflation leads to higher interest rates. In addition, the impact on the balance sheet hinges on how interest rates and spreads react on inflation, as well as on the maturity (mis)match between assets and liabilities.

Given the importance of the claims channel, it is not surprising that the p&c business is first and foremost to suffer from an inflation shock. In particular, casualty and other long-tail businesses are on the hook as they are characterized by long settlement periods: in general liability, for example, after three years of occurrence only half of all claims are settled; as a consequence, loss reserves have to be increased markedly in times of rising inflation.

However, note that claims inflation is only partially driven by general inflation. The other drivers are exposure growth (eg. higher economic activity), social inflation (eg. significant increases in jury awards and defense costs), new technologies (particularly in health) and rising natural catastrophes (particularly in property). In Germany, for example, general inflation has historically accounted for only around 40% of claims inflation on average. In certain lines of business, however, it is much less; this applies not only to health, with its huge strides in advancing medical treatments, but also to less obvious candidates such as motor: Over the last seven years, thanks to new materials and technologies (e.g. sensors), prices for car repairs increased by +4.1% p.a. against general inflation of +1.1% p.a.

The impact of inflation may be further diluted if it leads to a recession (stagflation scenario) and thus lower exposure growth.

The impact on the balance sheet is rather small in p&c if inflation and interest rates move in sync. On the liability side, nominal reserves are adjusted upwards (for inflation) and discounted downwards (higher interest rate) at the same time; on the asset side, the impact is negative but not big due to a generally shorter duration of assets and liabilities – and will be offset by higher investment income.

In general, the life business is a long-tail business as some policies (eg. pensions) can even last for many decades. Nonetheless, the impact of inflation is diluted for a simple reason: most life products come with benefits fixed in nominal terms. But there are some exceptions – eg. business lines like long-term care or disability – in which benefits increase in line with rising costs of living over a long time period.

But all in all, the indirect impact of inflation on the life business looms larger: With an inflation surge, lapse rates are likely to increase and demand for policies to decrease as rising inflation and interest rates erode the value proposition of fixed benefits and render guaranteed rates of return inadequate. The demand for savings products in particular might decline if the inflation increase is prolonged and other products (i.e. bank deposits) adjust faster. In the long run, however, higher interest rates are a positive for the life business. The impact on the balance sheet of life insurers is nil – if assets and liabilities are perfectly matched. But if liabilities have a longer maturity, the impact can even be positive because of the higher discount rate for future liabilities.

A forward-looking strategy to limit the negative impact of inflation on the liability side includes the indexation of premiums and deductibles, as well as the introduction of fixed payouts, limits and sunset clauses. However, on the asset side, ad-hoc mitigation strategies are possible, such as investing in inflation-linked assets or assets that generally benefit from higher inflation, such as certain equities: The resulting higher investment income would help to attenuate the negative impact of inflation on claims. However, the easiest way to restore profitability would be a quick reversion of inflation rates to the mean. So if the overshoot of inflation rates remains an episode, the impact on the bottom line should also be limited and short-lived.

The new risk landscape post Covid-19

Inflation might turn out to be a rather short-term consequence of the Covid-19 crisis. But other consequences will without doubt cause long-term changes. The risk landscape after Covid-19 will look very different.

However, this applies less to the major, long-term trends: Digitalization, the pivot to sustainability and the increasing polarization in politics, society and the economy – the most important keywords here are de-globalization and inequality – were already shaping developments before Covid-19. However, the crisis has given them a boost, in some cases a dramatic one. This is true not only for digitalization, where the push is most obvious: working, shopping and entertainment from home are now a matter of course for most people. But the crisis is also acting as an accelerator for the other trends. The shift in emphasis from efficiency to resilience, for example, has been accompanied by a reconfiguration of global supply chains that will lead, if not to de-globalization, then to a significant slowdown in the global division of labor. Covid-19 has also further increased social inequality as job losses have primarily affected the service sector, where young, female and foreign workers are disproportionately represented. On the other hand, the even greater focus on sustainability in the course of Covid-19 can certainly be assessed more positively. This applies in particular to climate protection: The decarbonization of all economic activities is at the heart of the major infrastructure programs aimed at stimulating economies post Covid-19.

However, the decisive change brought about by the pandemic took place and continues to take place at another level: There has been a fundamental change in the awareness and self-image and thus behavior of economic actors. This affects the state, companies and households alike.

For a long time – at least in developed countries – an (unspoken) leitmotif of social policy was to shift responsibility for financial risks from illness, job loss or longevity from the state and companies to individuals, at least partially. Covid-19 has led to a paradigm shift here. The state has clearly acknowledged its role as “risk taker of last resort” and has assumed the financial losses of the crisis for households (and companies) without compromise. Looking at the post-Covid-19 measures already taken and planned, not least in the US, it is easy to conclude that these aid measures are not a one-off, exceptional rescue operation; rather they point to a permanently changed self-image. The measures mark the return of the strong state, which uses its resources – (borrowed) money and (legal) interventions – to actively shape the economy and society according to its ideas and concepts. Social and economic outcomes are no longer to be accepted merely as the result of market activities. Of course, other developments, such as the increasing systemic competition with China and the rise of populism, have also contributed to the resurgence of the strong state but Covid-19 was the decisive impetus to make this policy mainstream. And once in the mainstream, it is not expected to disappear quickly.

What does this mean for insurers? For one, quite mundanely, more intrusive regulation is to be expected. The new regulatory approach is no longer "just" about transparency, information and risk management, but about conduct and "value for money": Do the products and services meet customers' expectations and needs? However, the industry should see these new requirements not as a chore, but an opportunity for real cultural change, which will pay off in the medium term: better products, stronger reputation, higher customer loyalty, thanks to true customer centricity, which runs through the entire company, from bottom to top.

On a fundamental level, however, the return of the strong state could become a threat to the insurance industry. The pandemic in particular has drastically demonstrated the limits of (private) insurability. How the industry deals with this will be crucial to its future significance. This is not just about insuring pandemics; risks from natural catastrophes and cybercrime can also quickly reach systemic dimensions. The industry must resist the temptation to shirk its responsibility by restricting cover and tightening wording. Instead, it should actively work on viable solutions which, in the case of risks of this magnitude, will result in private-public partnerships. It is essential for its role in society that the insurance industry actively contributes to the efficiency and effectiveness of such insurance regimes for systemic risks. Otherwise, its "license to operate" could increasingly be called into question.

Corporate thinking has also changed in the pandemic. The keywords here are “purpose-driven” or “stakeholder capitalism”. Today's companies serve a broader range of interests beyond maximizing shareholder returns; ideally, they are guided by a purpose, contributing to societal well-being by providing solutions to the societal problems facing their customers. This automatically leads to a stronger politicization of companies, as can be seen, for example, in their involvement in the "Black Lives Matter" movement.

This shift in emphasis in the self-image of companies also has an impact on their demand for risk protection. Questions of reputation and brand are gaining great importance and new explosiveness, requiring not only new insurance solutions, but also joint strategies for managing and preventing risks. What is required is a holistic approach consisting of consulting and financial protection. In the context of accelerated digitization, data integrity issues naturally also play a major role, from the handling and use of private data to protection against cyber-attacks. New solutions are needed here, particularly with regard to working from home, not least in the area of worker compensation.

From the insurance industry's point of view, however, the greatest changes are to be observed among households, i.e. retail clients. The often traumatic experiences during the pandemic have led to an appreciation of central insurance concepts such as protection and safety, resilience and wellness. This has been accompanied by increased demand for risk solutions, not least in the area of health.

However, this is by no means synonymous with a run on traditional insurance policies by customers. Rather, the opposite is likely to be the case. Because in the pandemic, even the last analog customers have had a crash course in digitization and have learned to appreciate and love the innovative, fast, and personalized offerings of digital providers – standards that they now also apply to their insurance. This means that insurers face no less a task than redefining customer engagement and experience, areas in which they have traditionally not exactly shone. One way to do this is to build ecosystems that offer not only insurance products but also related services, such as data-based services in mobility or consultations, prescriptions and self-management tools related to health. For this, cross-industry cooperation might become necessary. In this way, the value proposition of insurers would be enhanced, from pure financial compensation to risk management and holistic service offerings to prevent and mitigate risks. This would enable them to catch up with the established digital providers, which have been achieving a high level of customer engagement for years and are thus also in a position to create new products and services with customer-centric data ("value co-creation").

Covid-19 was a hard blow for insurers. The post-Covid-19 risk landscape, on the other hand, offers great opportunities – but not for free. The demands on the industry have increased dramatically. This affects both the government that regulates the industry and the clients who buy its products and services. In both cases, it is about building and expanding partnership-oriented relational business models; this would need to be accompanied by a shift from a pure product logic to a more service-oriented business model. The next few years will show whether the insurance industry as a whole is up to this challenge. However, it does not have much time for transformation. It may not necessarily lose its role as a risk carrier but it will lose the competition for customers to big tech companies or new competitors.