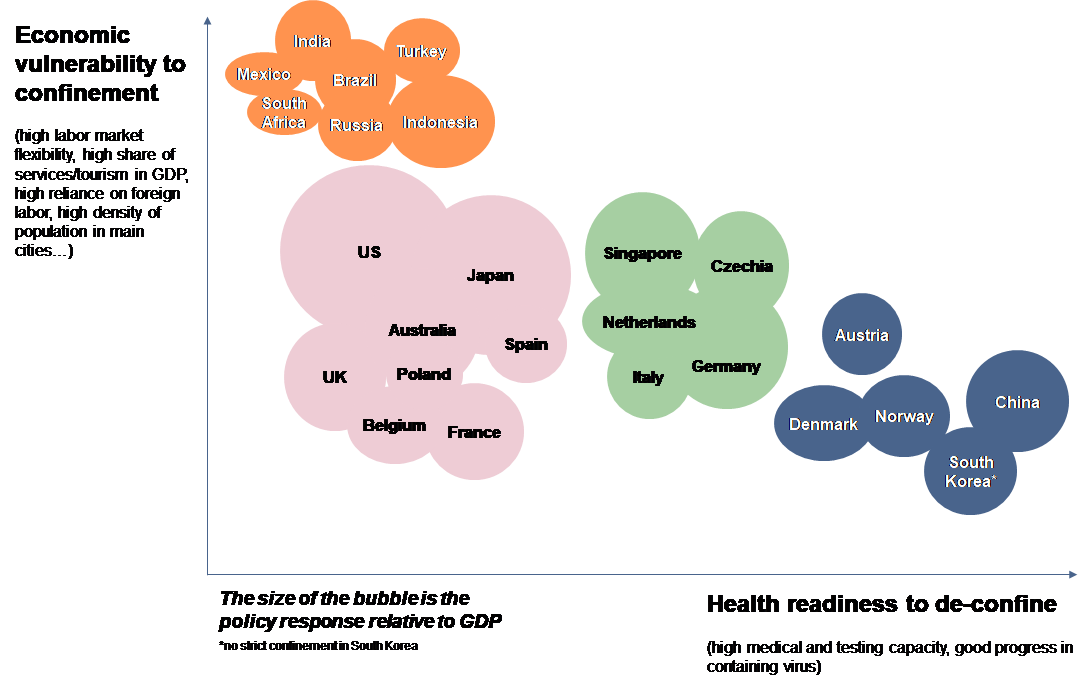

A second cluster, the early birds, are close to having defeated the virus, having ramped up testing capacity and medical capacity. They also showcase lower vulnerability than others, due to central top-down decision-making (China), efficient activity stabilizers and safety nets (Denmark) or limited confinement (South Korea). Their deconfinement strategies are likely to be prudent, and gradual, as seen by most recent announcements where some services subsectors remain shut until June. China’s experience shows confinement measures are being relaxed prudently or sometimes even re-tightened in cities where there is a risk of a second wave of infections, whether due to imported or asymptotic cases.

A third cluster comprises borderline countries, where progress has been made in stopping the virus’ spread (Italy) or medical and testing capacity has outperformed peers (Germany, Singapore). However, many of these countries are relatively more economically vulnerable to confinement than early birds. It is likely that here, in an effort to reduce the negative economic impact (through trade, tourism and industrial supply chains), deconfinement would come earlier or be less progressive; we would see higher risks of a new wave of infections (Singapore); it could be compensated only by a higher testing or contact tracing capacity.

The last cluster comprises countries still battling the epidemic and where testing has not yet reached the standard of best performers. In this cluster, we also find countries with highly dense urban areas (U.S., Japan, UK, France) where confinement is hard to enforce logistically. Besides, some are highly vulnerable in economic terms due to a flexible labor market (U.S.) and an already depressed economy (Japan) or limited fiscal policy leeway (Spain). Lastly, many countries are vulnerable to prolonged lockdowns because they have a high concentration in sectors where activity is halted. Optimally, deconfinement should be even more gradual and slow to avoid secondary outbreaks, and because some of these countries (mainly in the EU) have to deal with regulation before being able to implement contact-tracing apps. These countries could opt for on and off confinement intervals to make sure ICU capacity is sufficient to treat patients, testing is ramped up and self-isolation enforced strictly. The risk of deconfining too early because of economic urgency (e.g. Spain, which started lifting curbs on construction and industrial activity) remains.

Figure 3: Preliminary lessons for deconfinement: do’s and don’ts