Executive Summary

A (partially) done Brexit deal

After four and half years, three Prime Ministers and two general elections, Brexit finally took place on 31 December 2020 at 11pm. However, the deal with the EU is far from complete due to the lack of time for preparation, and lingering uncertainty has resulted in some disruption at the borders since 01 January 2021: many small firms have suspended EU imports and exports as they wait to see what Brexit-related changes would mean, according to the UK Federation of Small Businesses, and about one in five trucks have been turned away at channel crossings, partly because of Brexit paperwork, according to the UK Road Haulage Association.

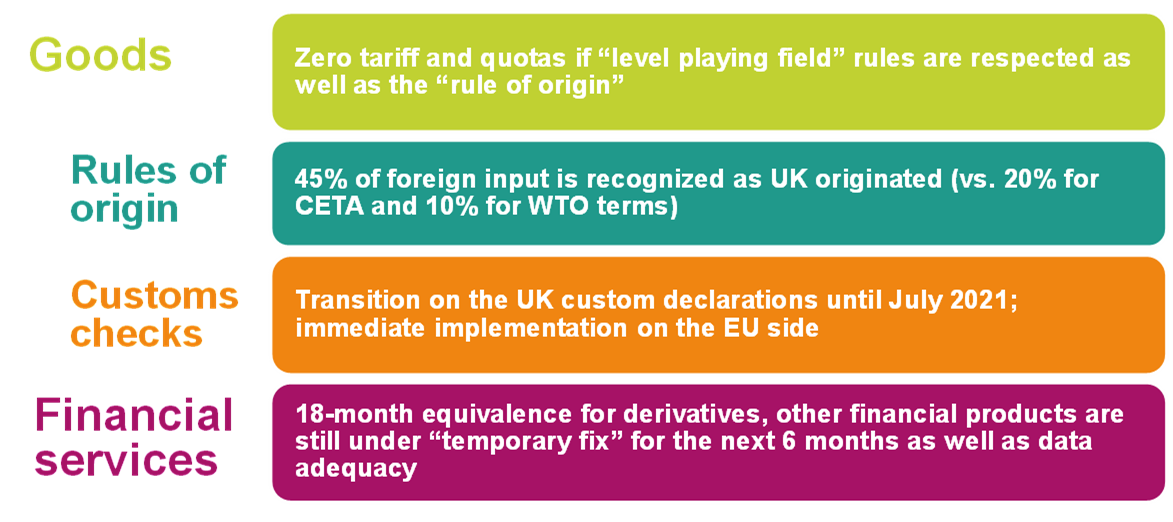

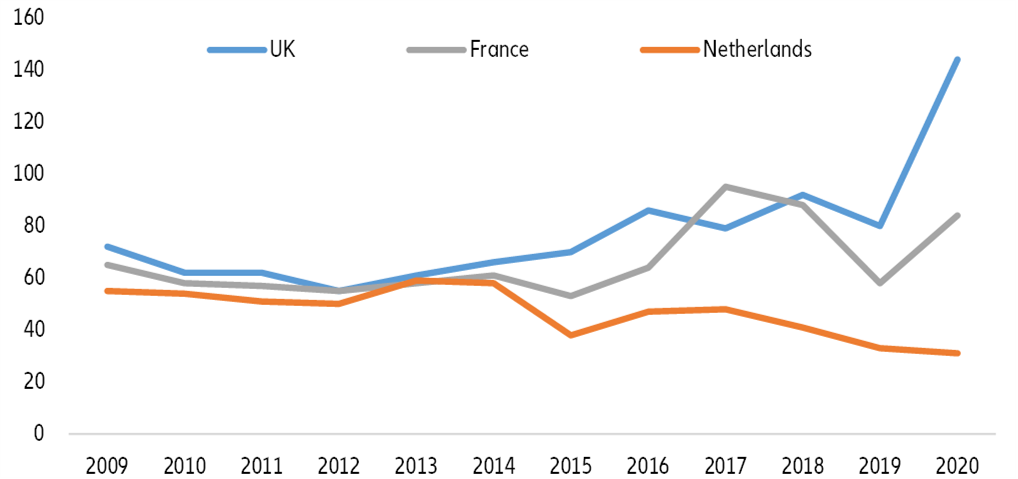

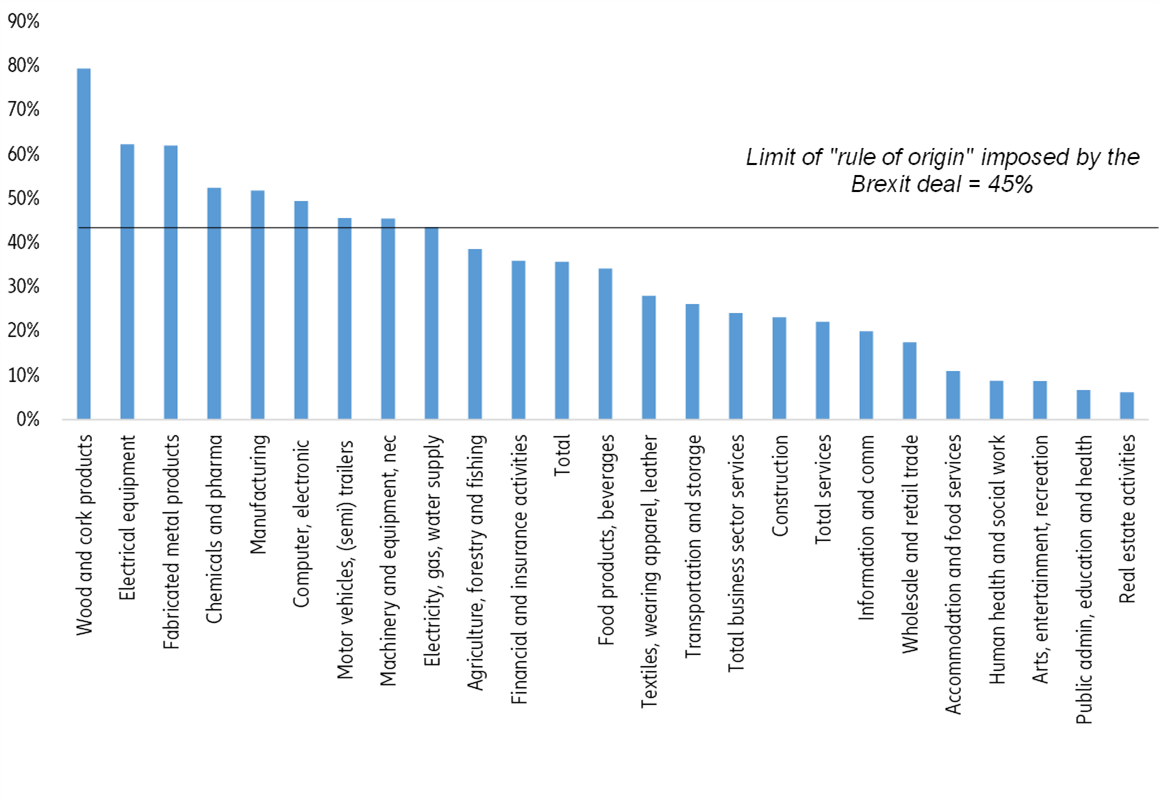

On goods, as expected, no tariffs will apply if the level playing field conditions and rule of origins are respected (see Figure 1). Indeed, if the UK moves too far from EU rules, notably regarding subsidies – which have increased over the past few years, see Figure 2 – and if the EU considers that this distorts trade and harms its businesses, a ‘”rebalancing mechanism” can unilaterally apply. This would mean tariffs are likely to be imposed in a similar way as the EU and the US implemented bilateral tariffs following their Airbus-Boeing dispute at the WTO. Financial services and data adequacy are still awaiting for equivalence from the EU and fall under a “temporary fix” of six months.

Cooperation on foreign policy, security and defense will be reduced below current levels, along with provisions for transport, energy and civil nuclear cooperation. Mobile roaming, mutual recognition of professional qualifications, access to legal services, digital trade and public procurement are other areas where cooperation will be downgraded. Indeed, both British and EU professionals wanting to practice abroad will need to get their qualifications officially recognized. Furthermore, while the EU and the UK have agreed not to require visas for travel, the free movement of people will end. That means EU citizens going to the UK, and vice-versa, will be subject to border screenings and no longer be able to use biometric passports to cross swiftly through electronic gates.

Figure 1 – The Brexit deal in short