As Italy’s next Prime Minister, former ECB President Mario Draghi starts with a double economic burden: weak growth momentum and a vaccination delay that could cost EUR10bn (0.6% of GDP). The risk of early elections now seems contained as Draghi will be heading a government of national unity, comprising technocrats as well as traditional politicians from left, centre-left, centre-right and right parties. However, the new government faces slowing growth momentum: Unlike in most other Eurozone countries, growth in Italy did not surprise on the upside in Q4 2020 (-2.0% q/q, -8.8% for 2020 as a whole) due to lockdown measures and the trend reversal in foreign trade. In Q1 2021, we expect economic output to decline again by -1.25% q/q. Meanwhile, the vaccination progress is currently too slow to allow for a significant easing of restrictions.

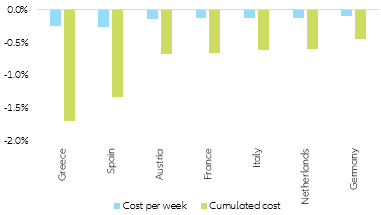

As in the rest of the EU, Italy has already fallen five weeks behind schedule for its target of vaccinating 70% of the adult population by the summer. In Italy, each week of delay equals EUR2bn in lost output.

Figure 1 – Cost of vaccination delay in the EU (output lost in % of GDP)

To deal with this situation, Draghi’s leverage will mainly be on the fiscal side. So far, the Italian government has been generous on guarantees but more cautious on stimulus measures (6.5% of GDP), especially when it comes to public spending. According to our (preliminary) growth forecast of +3.3% this year and +3.8% next year, Italy will be one of the last Eurozone countries to reach pre-crisis GDP levels in mid 2023, one year after the Eurozone as a whole. To catch up with its European peers, a fiscal package similar in size to that of 2020 would be necessary to boost GDP growth by at least 2pp this year. No rumors of a new package have leaked out yet, but Draghi will have to position himself here soon (upcoming end of redundancy ban and support for most exposed sectors). In the case of a new package, we expect more weight on the demand side (the previous was equally weighted). This is easier to achieve in a heterogeneous coalition, especially as the supply side should be covered by the national recovery plan.

Given the tight schedule, we don’t expect major changes in the size and orientation of the national recovery plan. Italy is one the largest beneficiaries of the “Next Generation EU” package, with grants of EUR82bn (5% of GDP). The implementation of the national recovery plan will be essential in getting the economy back on track. However, the last government broke apart over the design of the plan. The current draft includes expenses of EUR310bn over six years (EUR210bn from the EU recovery fund, EUR20bn from other EU programs and EUR80bn from national funds), of which 70% should be allocated to investments.

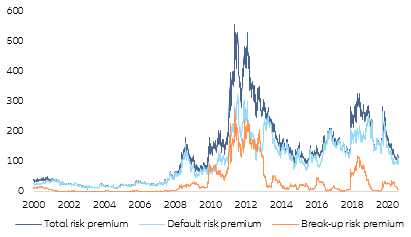

The weakness of the current draft plan is not its thematic focus (green transition, transport and digitalization), but rather its fragmented structure into numerous small- and mid-sized projects that are prone to operational frictions. Given the tight schedule (target date 30 April), major changes in size and general orientation are unlikely, but Draghi and Finance Minister Franco could provide more strategic guidance and specify governance here. In the negotiation with the Commission, we expect a cooperative approach. However, given Draghi’s heterogeneous coalition, tough negotiations might occur with regard to the reform counterparts. But we are also convinced that the communication will be handled with care. Draghi knows far too well that the biggest risk to the Italian spread lies in political uncertainty and open conflict with Europe. In advance of his appointment, the 10y spread vs Germany had already contracted by 20bp, bringing 10y yields to a record low of 0.50%. Concerns about Italy's remaining in the Eurozone have largely disappeared from markets: hardly any break-up premium is currently priced in (see Figure 2). Draghi in office is an additional, but not the only reason why we remain positive on the Italian spread until the year’s end.

Figure 2 – Italian spread pricing hardly any break-up risk

(decomposition of spread 10y Italy vs 10y Germany, in bp)

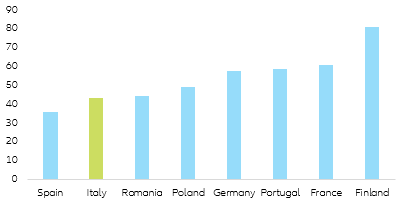

A historic opportunity to boost private and public investment, but implementation risks are sizeable. In the longer term, Draghi's success or failure will depend on the successful implementation of the recovery plan as well as the initiation of the reforms that come as a counterpart to the EU transfers. Italy has made advances in areas such as the pension and labor markets (Jobs Act), but weaknesses remain with regard to judicial processes, competition rules, red tape, labor participation, education and public sector management. These drag on productivity growth, which is particularly weak in Italy (only 0.1% on average over the last five years). Italy’s weakness in public management is reflected in its mitigated track record in public investment in general and EU projects in particular. In the 2014-20 EU budget period, Italy only spent 43% of the structural funds available, while the absorption rate in Germany and France was around 60% (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 – Italy struggles to spend EU structural funds

(share of structural funds from 2014-20 budget spent by September 2020, in %)

This contributes to the subdued development of Italy’s (net) capital stock, also weighing on productivity growth. In a context where deficits and public debt are less dominant in the public and European debate, and with cheap funding available, there is now a historical opportunity to boost private and public investment (a very different context from the Monti government of 2012, which was expected to deliver on fiscal consolidation). Corporate loans have already proven dynamic in 2020. Backed by generous state guarantees (35% of GDP in total), a seven-year period of deleveraging in the Italian corporate sector has come to an end (corporate debt to GDP rising from 68% of GDP in 2019 to 75% of GDP in Q3 2020). However, the task now is to transform this crisis liquidity support into long-term investment momentum. As to public investment, we would expect it to reach 3% of GDP this year as the disbursements from the EU recovery fund unfold.

Italy's recovery must be considered a central task of European economic policy as the public debt burden remains a weak spot. The

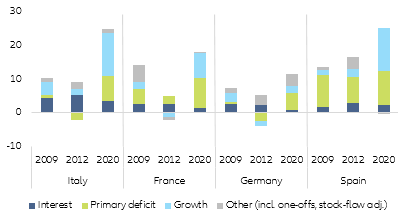

Covid-19 crisis caused Italian public debt to rise to 160% of GDP. This figure is likely to stabilize over the next two years at best. But if the recovery fund was to increase growth potential by 0.3% p.a. in the long term, then the debt level could return to its pre-crisis level in 20 years, assuming constantly low interest rates and a balanced primary balance. If the growth effect was 0.6% p.a. (which we see as the upper limit), pre-crisis levels could be achieved after 12 years. However, the increase of the debt-to-GDP ratio in the Covid-19 crisis was very different from the increases in previous crises. In 2020, half of it was due to the decline in GDP and only one third due to the primary deficit. In the euro crisis of 2012, a primary surplus was generated. The increase of the debt-to-GDP level was mainly due to the increase in the interest burden (rising risk premium). In 2009, the impact of interest payments and growth were similar in size (see Figure 4). The interplay of monetary and fiscal policy has given Italy the necessary space to respond to the crisis. Both must now continue to work together to mitigate the effects of the crisis. Draghi is ideally suited to strengthen the foundation here.

Figure 4 – Contributors to change in public debt-to-GDP in recent crises

(contributions to change in pp)

If Draghi is successful, he might bring Italy back at the forefront of European integration. But for Italy, participating in “Next Generation EU” means not only opportunities but also responsibility. Only if even the skeptical European partners can be convinced that the money will be well spent and not wasted can a long-term perspective of a common fiscal policy - the most ambitious joint economic project since the creation of the euro - open up. If Draghi proves up to this challenge, he might put Italy back at the forefront of European integration, including on topics such as public debt sustainability, the reform of the SGP (Stability and Growth Pact) and the progress of the Capital Market and Banking Union. Under Draghi, Italy could become an important intermediary between the fiscal orthodoxy reappearing in the North and the voices in favor of debt cancellation. We think that with regard to the SGP, Draghi could advocate a rather flexible position, probably favoring an approach combining monetary and fiscal policy orientation. When it comes to debt cancellation, a Draghi-led Italy is in our opinion unlikely to be supportive. In addition to the general monetary and legal reasons, a Draghi-led Italy might emphasize concerns about financial stability, given the significant exposure of its large banking sector to domestic sovereign debt. A potential confidence shock in government bonds risks having strong negative spillovers for Italian economy. The fiscal space gained from the debt cancellation could be consumed by bank recapitalizations.

Draghi is Italy’s silver bullet to prove its ability to reform. But Europe’s Hamiltonian moment will not only rely on Draghi’s capacity to implement the recovery plan. It will also depend on the containment of centrifugal forces in Italian politics. To achieve the goals mentioned above, Draghi needs to build a stable majority in both houses for the remaining legislative term (mid-2023). This isn’t a done deal: especially in the Senate, his support seems less widespread and the support of M5S is shaky. There is a risk that when the pressure of the pandemic fades, the fragile coalition of national unity could quickly disintegrate. If Draghi proves to be only a transitional figure who leaves the political stage involuntarily, this could have a lasting negative impact on the perception of Italy’s ability to reform by European partners and the financial markets. The positive confidence effect of the common borrowing effort would be quickly reversed, Euro sovereign spreads would widen again and the EU could find itself even more fragmented than before.