Emerging markets: Increased disparities

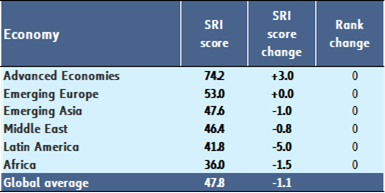

Systemic social risk in EMs as a whole has risen, and the high regional disparity that we discovered in 2020 has further increased. However, the ranking among EM regions remains unchanged (see Figure 1).

Emerging Europe

On a regional basis, overall social risk has remained comparatively moderate and unchanged over the past 18 months in Emerging Europe. However, there is a big intra-regional divide between richer and poorer countries. Nine of the 11 EU member states in the region have a SRI score of more than 60 and are on par with many AEs. This suggests that EU membership not only enhances prosperity but also social stability. Bulgaria and Romania are the exceptions, with SRI scores below 55. These two countries are the poorest EU members and they score particularly badly with regard to trust in government. This is reflected in the ongoing frequent government changes before the end of legislative periods and, in 2021, also in very low vaccination rates, despite sufficient access to jabs. Generally, most of the EU member states have also experienced a decline in social risk over the past 18 months (and thus an increase in their SRI scores). This can be attributed to strong fiscal stimulus (in the form of social spending), protection of the labor market and relative currency stability.

Higher social risk in Emerging Europe is a given in most CIS+ countries, some Balkan states and Turkey. Among the larger countries, Serbia scores relatively well with a SRI of 59.6 and rank 46. But Russia (rank 75) Ukraine (81) and Turkey (122) all have a SRI score of 50 or below, with sharp currency depreciations during the pandemic adding to the declines in consumers’ purchasing power. Apart from Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, Turkey remains the country most vulnerable to social risk in the region.

Emerging Asia

Emerging Asia continues to rank second on overall social risk at the regional level. The average regional SRI score decreased only slightly by -1.0pt to 47.6 over the past one and a half years. South Korea, China, Singapore, Hong Kong and Vietnam saw a significant decline in systemic social risk, likely for the same reasons as New Zealand and Australia, namely successful lockdown measures to contain Covid-19 (at least for a long time). Vietnam thus escaped the group of populous countries in the region with significant vulnerability to systemic social risk. India, Indonesia, the Philippines, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Pakistan remained in this group and Thailand joined it after a drop by -8.2pts in its SRI score since June 2020. The increase in social risk in Thailand reflects a sharp decline in real per capita income, exacerbated by a steep currency depreciation, decreased fiscal revenues and low social spending, as well as weakened governance indicators. In the region, Thailand’s drop in the SRI was only trumped by Laos (-10.6 pts), Afghanistan (-14.5 pts) and Myanmar (-14.9 pts). The two latter countries already posted poor SRI scores in 2020, suggesting high social risk, and the slump in this year’s scores obviously reflects the serious deterioration of their respective political situations.

Middle East

The Middle East region’s average SRI score has declined slightly by -0.8pts since spring 2020 to 46.4, keeping the region close on the heels of Emerging Asia. However, the disparity of systemic social risk between the six GCC member states and the six non-GCC states has further increased since the beginning of the pandemic. The GCC states have SRI scores between 51.3 (Bahrain, rank 69) and 68.7 (Qatar, rank 24), suggesting moderate to low risk. All of them are high-income economies and, like AEs, they all experienced a slight decline in social risk, mainly reflecting more stable real per capita incomes compared to other EMs, thanks to stable exchange rates (currency boards) and low inflation rates.

Among the non-GCC states, Iraq and Lebanon saw the largest declines in their SRI scores. The two countries also experienced the sharpest real GDP contractions in 2020, by -15.7% and -25%, respectively. Iraq’s SRI score dropped -10.1pts to 29.5, lowering the country to rank 162 (from 135) in our analysis. This was mainly driven by two developments: (i) the shift from a small double surplus in the fiscal and current accounts to a huge double deficit in 2020 amid low oil prices and (ii) the -18.5% devaluation of the Iraqi dinar at the turn of the years 2020 and 2021, which led to a +20% increase of the prices of basic foodstuffs. The former triggered the latter and also caused a low level of social spending to mitigate the impact of Covid-19. Meanwhile, Lebanon’s SRI fell -8.8pts to 28.7, moving it to rank 166 (from 148). This reflects the full breadth of the domestic political, economic and financial crises ongoing in the country: economic activity and labor force participation have plunged, governance indicators fell substantially and the purchasing power of consumers dropped dramatically due to the currency decline.

Latin America

Latin America is the region where systemic social risk has deteriorated the most, indicated by the -5.0pts fall in the average regional SRI score to 41.8. This is not surprising in the context of its sharp currency depreciations and often weak government responses to the pandemic. Only six out of 31 countries have recorded a better SRI score this year: Chile, Mexico and four small economies with minor improvements which nevertheless remain in the high social risk category. Chile and Mexico have both improved by +3.5pts, thanks to increased fiscal revenues and social spending, a decline in perceived corruption (though the level remains very high in Mexico) and a smaller currency depreciation as compared to the spring 2020 survey, such that prices for essential goods have not increased as much as elsewhere. Sentiment in Chile may also have benefited from the rapid vaccination rollout in the country. However, while Chile’s overall SRI score has moved above the 50 points mark and the country is assigned rank 72 in this survey (up from 96), Mexico continues to face high social risk with a SRI score of 36.4 and rank 136 (up from 160), even though it has overtaken Brazil (rank 142), Colombia (rank 151) and Peru (rank 154). The latter is the biggest loser in the region over the past 18 months, having dropped -13.6pts to a score of 31.0, trailed in the region only by Nicaragua, Venezuela and Haiti. Peru’s fall reflects a sharp currency depreciation, lower fiscal space and spending and weakened governance indicators. This has occurred against the backdrop of the presidential election in March 2021, which was heavily contested and marked by strong instability as the opponent claimed victory over the current president, the far-left Pedro Castillo. Although the situation has improved, there is still a heightened risk of political instability and the policy shift presents new risks to firms. Castillo’s election has already led to substantial capital flight and contributed to the depreciation of the Peruvian sol.

Overall, the sharp deterioration in systemic social risk in Latin America, spread over many countries, suggests that more public protests cannot be ruled out in the region over the next two years or so.

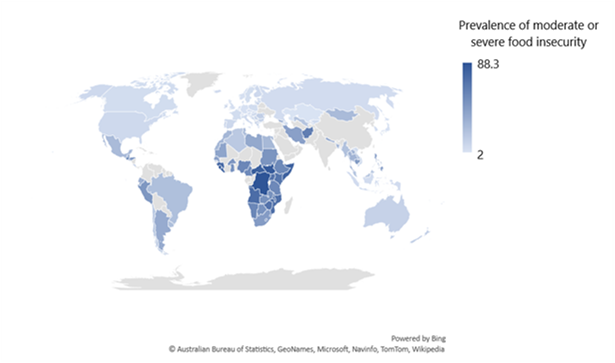

Africa

Systemic social risk remains the highest in Africa according to our updated analysis. However, it has not substantially increased during the pandemic. The continent continues to be the weakest region with an average score of just 36.0, slightly down by -1.5pts compared to spring 2020. Only three out of the 53 African countries score above 50.0: Seychelles (rank 51, up from 111, thanks to a +12.0pts improvement), Cape Verde (rank 60) and Botswana (65). The next best ranked countries in the region are Egypt (78), Namibia (84) and South Africa (88), with the two latter making big leaps in the SRI score over the past 18 months (+7.9 and +6.4pts, respectively). This may be surprising at first sight, especially the case of South Africa. The main driver of the improvement was a strong recovery of the closely correlated currencies of the two countries after the initial shock at the beginning of the pandemic, which has helped to contain imported inflation. Additionally, increased social spending has been supportive.

On a negative note, seven of the 10 worst-ranked countries are in Africa. These include failed states such as Congo DR, Sudan, South Sudan and Zimbabwe, but also the major oil exporters Angola and Nigeria, which have not been able to turn windfall oil revenues into economic welfare for the entire population.

Drawing the balance of Covid-19 economic policy responses

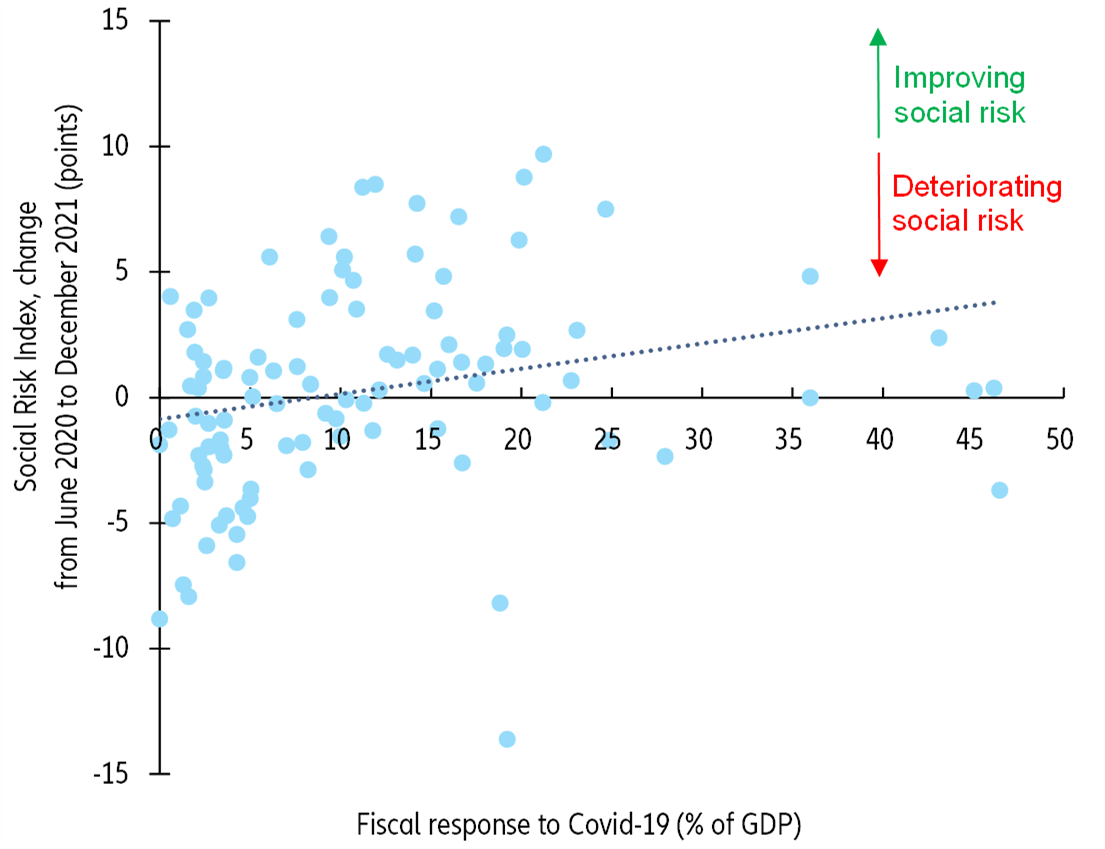

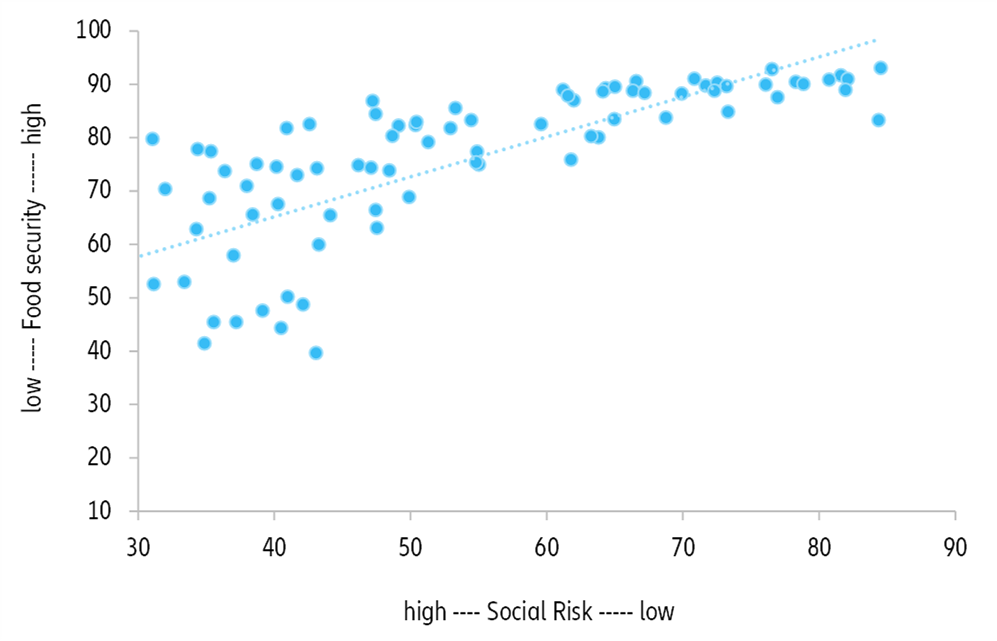

Looking at social risk in the context of countries’ fiscal responses to Covid-19 suggests that there is a loose correlation of +25% between the size of countries’ fiscal stimulus measures and the change in our SRI scores across our sample of 185 countries (see Figure 2). This indicates that on trend social risk mostly declined in countries with a strong fiscal response and vice versa.

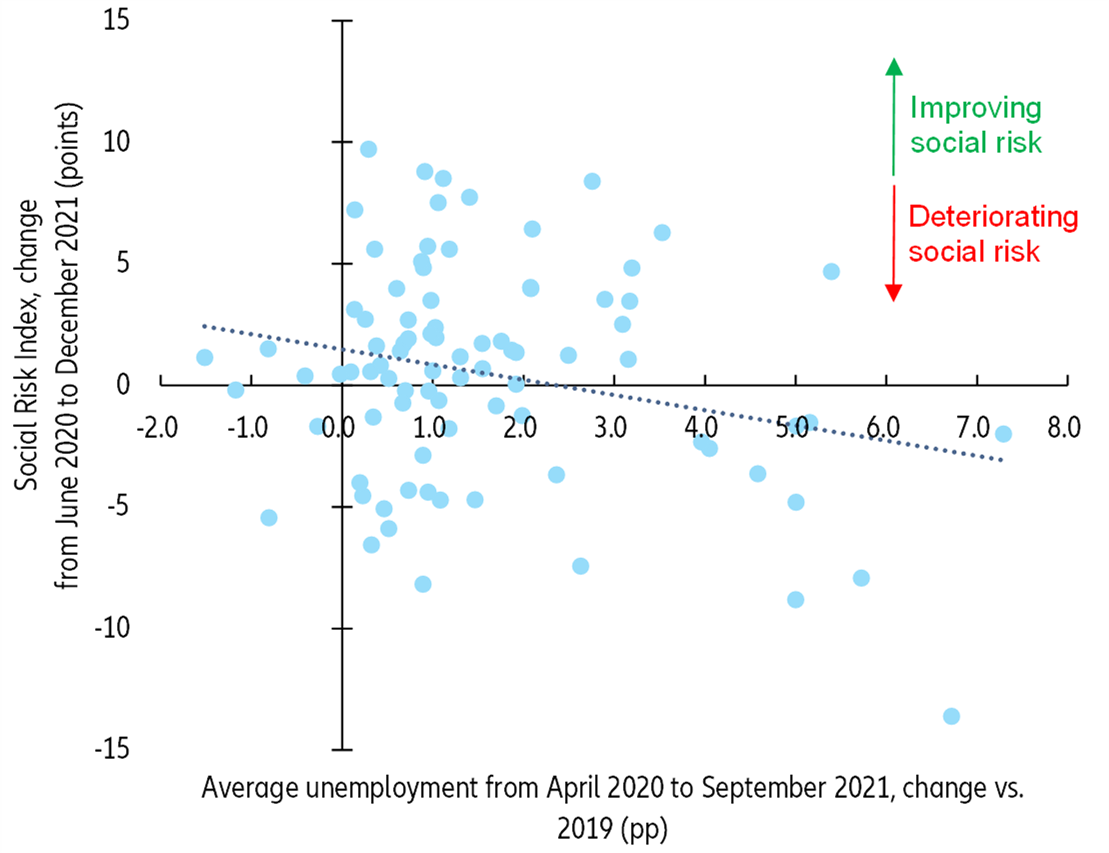

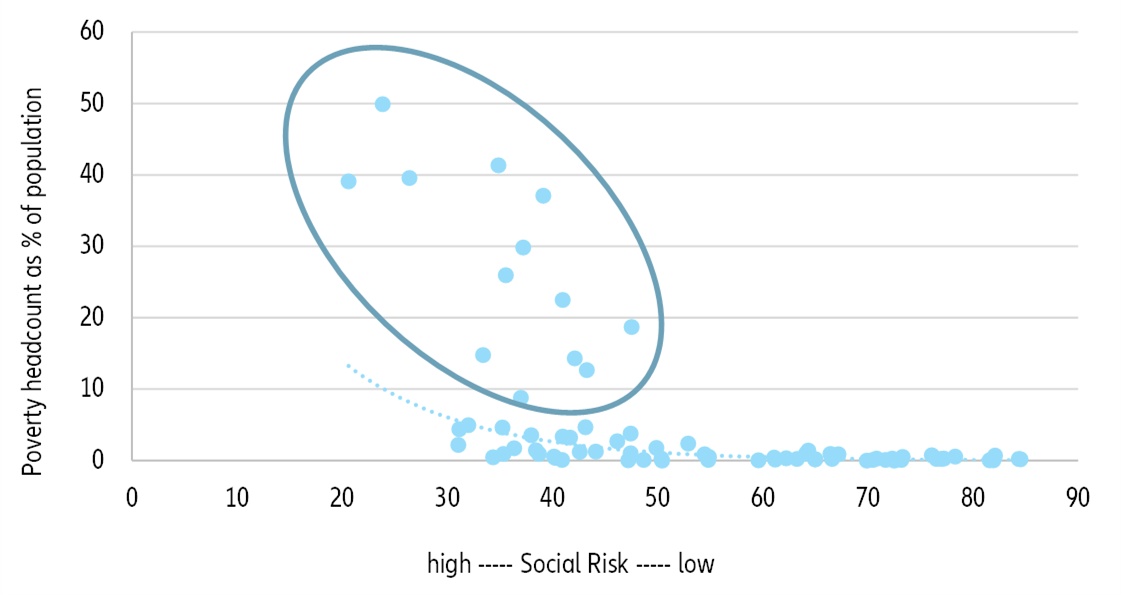

Moreover, looking at social risk in the context of rising unemployment in 2020-2021, we find a loose negative correlation of -24% between the change in unemployment and the change in our SRI scores (see Figure 3). This means that, on trend, the more the unemployment rate rose, the more social risk increased, and vice versa.

Figure 2: Correlation between the fiscal response to Covid-19 and changes in the SRI