In Asia-Pacific, we now expect aggregate growth for the region to decline to -1.3% in 2020 (down from -0.6% expected in April, and compared with +4.3% in 2019). This downwards revision is driven mainly by lower GDP growth forecasts in

India (-3.3% ),

Indonesia (-1.5%),

Thailand (-6.0%),

Hong Kong (-5.9%) and

Singapore (-5.1%). The changes are due to stricter and/or longer lockdown measures to contain the pandemic, and sometimes underwhelming policy responses to lead the economy towards a recovery. Idiosyncratic factors are also at play. In

India, despite the significant cut in our forecast, risks remain on the downside. In particular, a pandemic not yet under control means that activity resumption could be even slower than in other economies, and could also imply the risk of new virus outbreaks. The policy leeway is limited by twin deficits and a vulnerable financial system. In

Hong Kong, protests resuming faster than previously expected in the context of a pandemic will further delay the economic recovery (e.g. in the tourism and retail sectors).

The U.S. potentially imposing the same tariff hikes on

Hong Kong as the ones applied on mainland China over 2018-19 should have a limited impact (less than 1% of Hong Kong GDP). At this stage, we keep the central scenario that implementation of the national security law will not materially impact Hong Kong’s business environement. On the positive side in the Asia-Pacific region, we have revised up 2020 GDP growth forecasts for economies that have experienced looser and/or shorter lockdowns than initially expected. That is the case for

Australia (-4.3%),

New Zealand (-4.8%),

South Korea (-1.5%) and

Taiwan (-0.3%). These economies could also be supported by the comparatively earlier recovery of the Chinese economy. Trade data show Asia-Pacific exports to China outperforming those to the U.S. or the Eurozone.

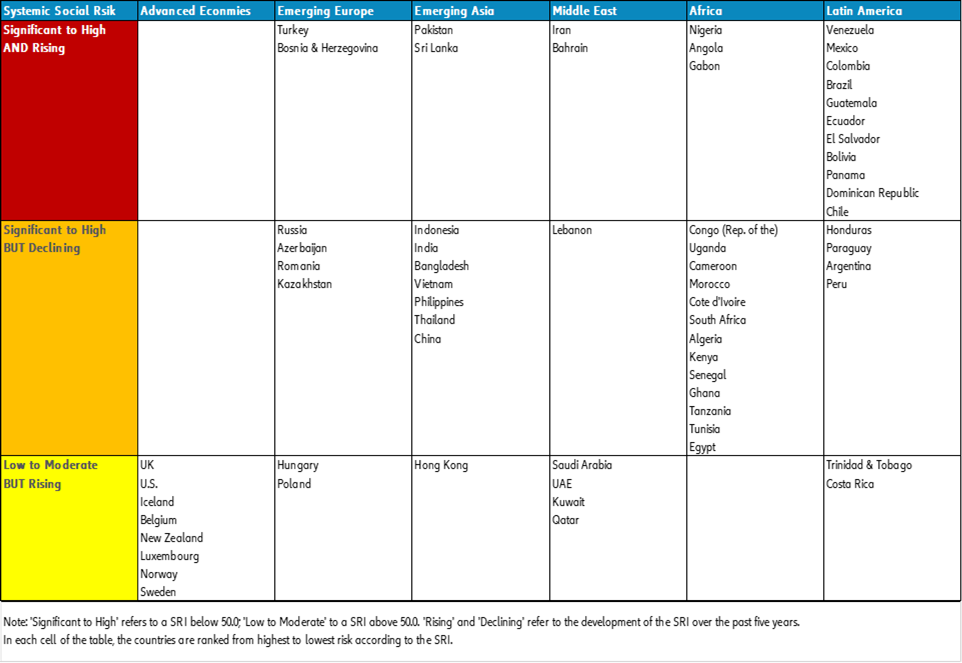

Latin America is a laggard overall, but the crisis exacerbates regional differences

The region will emerge as a laggard, but the crisis should also accelerate the divergence between countries that had favorable initial conditions (low debt ratios, sound business environment, etc.) and the others. All major countries will fall into a deep recession as we revised our 2020 regional forecast downwards from -4% to -6.5% and project a modest 3% rebound in 2021. This is due to a more severe spread of the pandemic than projected in March, and stringent and/or prolonged lockdowns. Yet Peru, Uruguay or even Colombia to a lesser extent should probably emerge with fewer vulnerabilities and a better momentum than

Brazil and Mexico. For the region, stimulus is at work and the credit crunch is avoided for now, yet we believe it will not be sufficient to avoid massive employment losses and insolvencies in the region.

Last March, we anticipated the recession in

Brazil and high number of insolvencies and expressed doubts about the administration's ability and willingness to manage the crisis. We now forecast the deepest yearly contraction in

Brazil’s history (-7%). As of June, despite the reopening, confidence has barely recovered and activity is still 26% below pre-crisis levels, which signals a sluggish recovery. Localized lockdowns are still possible. Second, Brazil’s vulnerabilities lie in its political and social risk, which is on the rise: the economic policy uncertainty index is at a three-year high. The crisis and its emergency funding needs rendered previous fiscal efforts obsolete. Political gridlock risk is higher than ever, and even the likelihood of impeachment after the crisis is rising, which could prolong the downturn.

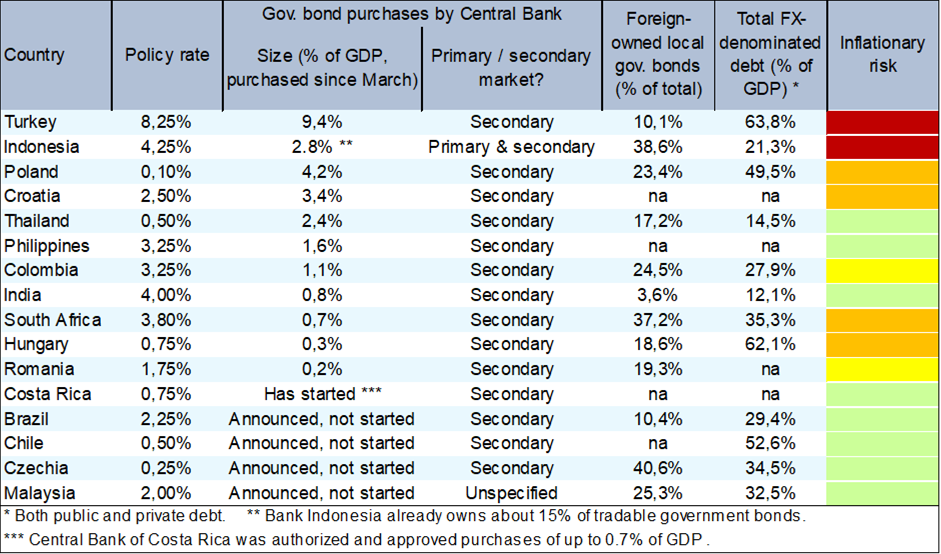

Emerging Europe: an unequal policy support to continue over the next two years

In the Emerging Europe region as a whole, annual real GDP is forecast to contract by -5.3% in 2020, followed by a moderate recovery to +4% growth in 2021. By and large, the curves of Covid-19 infections have flattened in most countries of the region for now, and lockdowns are gradually being eased. At the same time, monetary policy accommodation and fiscal stimulus have supported the economies, albeit to diverging degrees as there is uneven room for policy leeway. We expect the unequal policy support to continue over the next two years.

Czechia and

Poland are expected to stimulate the most. Both have announced large fiscal stimulus programs and lowered monetary policy interest rates close to zero. The Polish central bank has also purchased a noteworthy amount of government bonds (equivalent to just over 4% of GDP to date) on the secondary market to ensure a smooth functioning of bond markets. Meanwhile

Slovakia, Slovenia and the Baltic countries will benefit from their Eurozone membership. Russia has cut its policy rate to a record low 4.5% but is reluctant to use its large sovereign wealth fund assets massively to stimulate the economy, keeping them as a last resort in case of need. Less room for policy manoeuver is available in Turkey, Ukraine,

Romania and

Hungary, which will remain the higher risk economies in the region. In particular, the Central Bank of Turkey’s purchase of government bonds on the primary market (1.1% of GDP), along with the burning of 30% of its FX reserves through massive intervention in currency markets to stabilize the TRY, bears the risk of raising inflation, further deteriorating investor confidence and triggering another balance-of-payments crisis, just two years after the previous one. In the medium term, the uneven room for policy manoeuvering combined with differing momentum at the start of the crisis, as well as individual countries’ dependence on exports and tourism, will determine the depth and length of the recessions. Poland should reach its pre-crisis level of GDP at the end of 2021,

Czechia and

Turkey in mid-2022 and Russia only in 2024, mainly due to its overall lower growth regime.

The triple shock of Covid-19 in the Middle East will have long-lasting effects

In the Middle East region, the triple shock of Covid-19, the oil price slump in H1 2020 and the response to the latter – oil output cuts began in May – will hit exports and growth hard, in particular in the hydrocarbon-dependent economies. Stringent confinement measures against the spread of Covid-19 are being eased only very gradually, impacting domestic demand and tourism revenues markedly. Moreover, the oil price and output crisis will result in huge export losses in the oil-exporting countries. For example, these losses are forecast at more than -USD100bn in 2020 in both in

Saudi Arabia and

the UAE. And only one fourth of these shortfalls will be regained in 2021. As a result, annual real GDP in the Middle East as a whole is projected to decrease by -6.8% in 2020, followed by only a modest recovery to +2.2% growth in 2021. Another result is that fiscal and current account deficits will widen sharply in the GCC countries in the next two years. This is still manageable for Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar and Kuwait, which have ample FX assets in their SWFs. But it will be a problem for Bahrain and

Oman, whose reserve assets are much smaller and which therefore face increasing country risk.

Covid-19 crisis puts debt sustainability at risk for several African countries

In 2020, African GDP is expected to contract by -3.1%, which will be the first recession on the continent in 25 years. The strongest contractions will be seen in oil-exporting countries such as Nigeria (-3%), Angola (-4.7%) and Algeria (-6.7%). Restrictions on tourism will affect growth dramatically in Tunisia (-3.9) and Morocco (-3.9). South Africa is expected to go through one of the sharpest recessions on the continent (-7.8%) as a result of an unprecedented demand shock (internal and external) and capital outflows. The Covid-19 crisis also will put debt sustainability at risk in highly indebted countries such as Angola, Egypt, Tunisia. In 2021, we project Africa’s GDP to rebound by +4%, with the support of stronger global demand, higher commodity prices and resuming tourism activity.